cross-posted from: https://lemmy.ca/post/39298754

I realize this community generally favours proportional representation, but I'm curious to hear your thoughts on a different approach to the problem of 'unrepresentative government'.

I question whether the goal of proportional representation, "every voter has 'their representative'", actually achieves what I consider to be a higher goal, "the government represents the interests of as many voters as possible".

If:

- you have a perfectly 'proportionally representative' parliament

- 51 of 100 of seats in said parliament are needed to form government

- winning seats as a single party requires difficult campaigning

- adding a party to a coalition requires difficult negotiation

Then anyone trying to grow a party or coalition with the goal of forming government will stop growing the coalition once they get 51 of 100 seats, because growing the coalition further requires difficult campaigning or negotiation, but yields no further benefit to the members of said coalition (since they would already have a majority at that point).

So even with PR, you still end up with a government that caters to a narrow majority and ignores social and economic problems that impact people outside that majority.

My solution, "a block of seats awarded in a nationwide winner-take-all Score Voting election," approaches this problem differently:

- electing the ruling party directly,

- and using Score Voting, where voters give each candidate a numerical score on an independent scale (note that Score Voting =/= Ranked Voting: a voter can give two different candidates the same score on the same ballot),

- where a party can have 60% support and yet lose to a party with 70% support,

- incentivizes candidate parties to try to exceed a 'mere majority' by as much as possible,

- because a majority is no longer enough to guarantee a win,

- because parties can no longer count on their own supporters exclusively supporting them.

I argue for Score Voting, but my rationale applies to Cardinal Voting systems in general.

TLDR: Score Voting is good.

Canadians want national unity.

The ideal of the Good Parliamentarian claims that politicians should, once elected, represent all their constituents and not just their core base, and that a governing party should, once elected, represent the nation as a whole, and not just their members.

So why is national unity a fleeting thing that emerges only in response to external threats, like American rhetoric about annexation and economic coercion, and why does it dissipate and devolve into factionalism once the threat is resolved (or when political campaigns simply drown the threat out)?

Because the Westminster System, in its present form, is institutionally biased towards division.

There are two reasons:

- Within individual constituencies, a narrow majority of voters is enough to guarantee a win, and

- In Parliament, a narrow majority of constituencies is enough to form government and pass law.

These have a common root cause:

Acquiring a narrow majority of something is the most efficient way to achieve the maximum reward.

If the easiest path to a win is to get the support of half-plus-one, who cares if you alienate everyone else on the other side?

The Solution: the Score Bonus System

This proposal suggests an incentive-based solution to create national unity:

The Score Bonus System: award a winner-take-all block of seats to the party that achieves the highest average score nationally in a Score Voting election.

Under this system, Canada's existing single-member districts are replaced with about half as many dual-member districts, each containing one 'constituency' seat and one 'national' seat.

In each district, candidates stand either as a 'constituency' candidate or as a 'national' candidate.

Voters mark their ballots by assigning numerical scores between 0 and 9 to each candidate, where higher scores indicate stronger approval.

Unlike ranking systems, this allows voters to express support for multiple candidates simultaneously.

Sample Ballot, Mapleford North, filled in by a sample voter

Seat Party Candidate Score (0 to 9) Constituency Brown Party Jaclyn Hodges 5 Taupe Party Dexter Preston 0 Independent Cecelia Olson 9 Janice Fritz 5 National Brown Party Isreal Robles 7 Gale Sloan 8 Taupe Party Royce Brown 0 Beige Party Billie Burton 9 Each district's 'constituency' seat goes to the 'constituency' candidate with the highest average score in the district.

The collection of all districts' 'national' seats form the 'winner-take-all' block, which is awarded in full to the party with the highest nationwide score.

When a party has multiple candidates competing in the same constituency:

- When computing nationwide averages, the score of its best candidate in each constituency is used.

- If the party wins the highest nationwide average, its best candidates from each constituency win the 'national' seats.

However, if no party achieves a national average score of at least 50%, the 'national' seats instead go to the 'national' candidate with the highest average score in the constituency, effectively falling back to the 'constituency' method.

Seat Type Breakdown

Seat Type Seat Count Winning Candidate From Each Constituency Constituency 172 (one per constituency) 'Constituency' candidate with highest score within constituency National 172 (one per constituency) If any party has >50% approval nationwide: best 'national' candidate from party with highest score nationwide; otherwise: 'national' candidate with highest score within constituency Total 344 (two per constituency) Example Election Results

Constituency Results, Mapleford North

Seat Party Candidate C. Score N. Party Score Constituency Brown Party J. Hodges 65% N/A Taupe Party D. Preston 20% N/A Independent C. Olson (Constituency Seat Winner) 80% N/A J. Fritz 70% N/A National Brown Party (Winning Party) I. Robles (Eliminated by G. Sloan) 65% 75% G. Sloan (National Seat Winner) 75% Taupe Party R. Brown 15% 55% Beige Party B. Burton 80% 65% National Results

Constituency Brown Party Score Taupe Party Score Beige Party Score Mapleford North 75% 15% 80% Rivermere South 70% 70% 20% Ashbourne Springs 80% 55% 25% ... National Average 75% (Winner) 55% 65% Takeaways from example election results:

- All three parties exceeded the 50% minimum average score threshold to be eligible for the 'national' seats.

- C. Olson, an Independent, won the constituency seat for Mapleford North by having the highest average score (80%) of any candidate in the constituency. The next best constituency candidate was J. Fritz, a fellow Independent, who got an average score of 70%.

- The Brown Party won all 172 national seats by having the highest national average score (75%) of any party in the nation. The next best national party was the Beige Party, which got a national average score of 65%.

- The Brown Party ran two candidates in Mapleford North: I. Robles and G. Sloan. Of these candidates, G. Sloan had the higher score, of 75%, so I. Robles was eliminated and G. Sloan contributed his 75% constituency score to the party's national average.

- G. Sloan was the surviving 'national' candidate nominated by the Brown Party in Mapleford North. Because the Brown Party won all national seats, G. Sloan won the 'national' seat for Mapleford North.

- Candidates running for constituency seats do not affect the scores of national parties

Why This System?

Consider two things true for all elections:

- Winning votes is expensive.

- The candidate with the most votes wins.

If a voter can support only one candidate at a time, then the cheapest winning strategy for a candidate is to acquire a slim majority, to the exclusion of nearly half the voters. Any more would be wasteful; any less no longer guarantees a win.

If a voter can instead support many candidates at a time, then a narrow majority no longer guarantees a win: all of a candidate's supporters may also approve of a competitor. A candidate with 60% approval loses to a candidate with 70% approval. This forces candidates into a competition not for the exclusive support of a narrow majority, but for the approval of as many as possible.

The only way a minority group can be excluded under electoral systems with concurrent voter support is if the minority group is so fundamentally incompatible with a candidate's current base that adding the minority would cost them more members from their current base than the minority adds. If adding the minority would result in a net increase in voter support, a candidate must include them, or lose to a competitor who does, even if that candidate already has the support of a majority. Because that majority might be just as satisfied with the competitor.

Electing single representatives

First Past the Post and Instant Runoff voting both fall into the first category (voters support one candidate at a time). Instant Runoff is effectively a sequence of First Past the Post elections; in each round, voters support their top choice. A narrow majority under either system guarantees a win. Hence, Division.

Compare with Score Voting. Voters support many candidates concurrently. Hence, Unity.

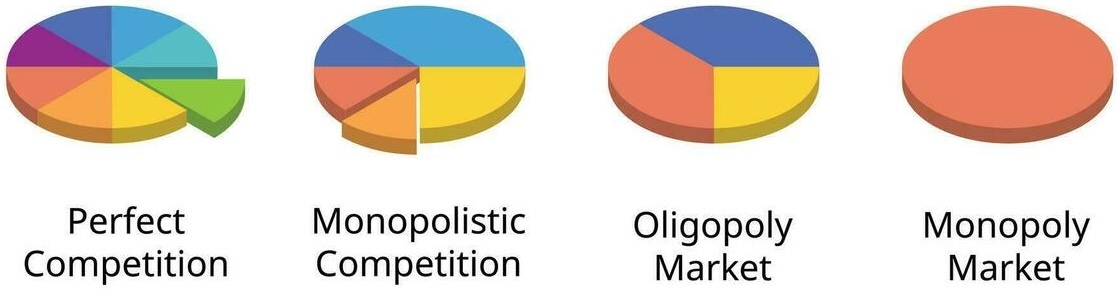

Electing multiple representatives

Traditional constituency elections, regardless how votes are counted within each constituency, and Proportional Representation both suffer from the same exclusive-voter-support problem as FPTP and IRV: Each seat is awarded to one representative, so parties and coalitions compete for a narrow majority within the legislature.

While Proportional Representation ensures the makeup of the legislature is proportional to the makeup of the electorate as a whole, it fails to incentivize the ruling coalition to include more than half of said representatives, or by extension, more than half of the nation. Therefore, as long as a ruling coalition is confident in its majority, it will ignore social and economic problems that impact voters outside of said majority, even in Proportional Representation.

Instead, the Score Bonus System creates a nationwide single-winner election to effectively elect the ruling party as a whole, and using Score Voting for this election creates an incentive for this party to include the interests of as many as possible.

Electoral Systems Review

System Optimal strategy Effect Single Seat FPTP Secure a narrow majority of votes. Division & Exclusion Single Seat IRV Secure a narrow majority of votes. Division & Exclusion Single Seat Score Appeal to as many voters as possible. Unity & Inclusion Traditional Constituency Elections Secure a narrow majority of districts. Division & Exclusion Proportional Representation Secure a narrow majority of voters. Division & Exclusion Score Bonus System Appeal to as many voters as possible. Unity & Inclusion Why combine the winner-take-all component with per-constituency elections?

Because:

- It maintains a constituency-first element to politics, even in the winner-take-all segment of Parliament. The ruling party, with a majority given to it through the winner-take-all segment, has a representative from each constituency.

- Allowing multiple candidates from the same party to run in the same constituency forces candidates to compete with fellow party members to best represent a constituency

- Having some seats that are elected only by constituency voters ensures each constituency has a representative accountable only to them

- The national seats only being awarded if a party gets >50% approval lets us fall back to conventional 'coalition government formation' with constituency-elected representatives if the winner-take-all election fails to produce a party with at least majority support. This avoids a party with, say, 35% nationwide approval, getting an automatic Parliamentary majority.

- Having both constituency and national elections occur on the same ballot avoids unnecessary complexity for the voters. Voters get a single Score Voting ballot.The ballot is as complex as is required to implement Score Voting, but no more complicated than that.

What next

I realize we're not getting Score Voting in Canada any time soon. It's not well known enough, and the 'winner-take-all block of seats' component may scare people away.

Plus, no politician content with their party having an effective monopoly on opposing the other side would ever consider supporting an electoral system as competitive as this.

Instead, I offer this electoral system to anyone who wants to take advantage of an "oh won't somebody do something" vibe to organize something, but wants to avoid their organization getting burned by the faulty electoral systems we have today.

A protocol for building a unified chapter-based organization:

- Launch regional chapters

- Each regional chapter randomly selects N interested participants, plus one or two 'chapter founders', to act as delegates to meet in a central location or online. The first conference will bootstrap the organization's 'internal parties'. Subsequent conferences evolve into a recurring networking event.

- Like-minded delegates, possibly assisted by 'political speed-dating', form 'internal parties'

- In each chapter, 'internal parties' nominate candidates for chapter and national seats.

- Each member scores each candidate in their chapter

- The highest scored 'chapter seat' candidate in each chapter becomes the chapter's local representative

- The highest scored 'internal party' across the organization as a whole wins one 'national' representative in each chapter

- Canadians, Unite!

Thoughts?

Thanks for the response! You're one of the first people to give feedback on it, so there's a few points I tried to make in the original post that, in retrospect, might have benefitted from some rewording.

I'll start with responding to this statement, since this is I think where the key of the argument for my system is, and then respond to everything else in-order.

The core of my argument was supposed to be that:

But evidently I need to rework my presentation.

The big idea

The basic idea behind Score (and Cardinal systems in general) is that multiple competing candidates can have the support of concurrent majorities.

Eg. Candidate A can have 70% support, and Candidate B can also have 70% support at the same time, because whatever the voters gave to Candidate A, the ballots do not prevent them from giving the same support to Candidate B. This distribution could come from:

So the incentive to exceed a majority is that once you have a majority, sure, you're now eligible for the winner-take-all mechanism, but you're not necessarily the only one eligible for it. So a candidate can believe they have 60% support, but knowing a competitor can also have 60% support at the same time, they are forced to broaden their campaign to 70% support, or 80% support, or as high as they can make it go until the next vote gained is two votes lost.

Whereas in FPTP, voters can support only one choice (meaning voters' support is exclusive, so majority = win), and in ranked systems, the general philosophy is to support your first choice exclusively (again, majority = win) unless the first choice would be a wasted vote, in which case they move on to their second choice.

I think my argument may have been more clear had I described the system with Approval Voting, which allows voters to approve of multiple candidates but not to describe how much they prefer one approved candidate to another, and then said in a footnote that Score Voting has the added bonus of 'degrees of support', but that this bonus isn't required to create the overall incentive structure I describe.

I somewhat agree.

They look similar in terms of what seats exist - both systems have 2-member constituencies, with one member assigned by the results of a local ballots, and another member assigned by the results of all ballots nationwide.

But my system differs in terms of how the seats are assigned, and what ballots the voters are given: In MMP, voters get a first-preference ballot, with mine, voters get a Score ballot, and the national seats are 'winner-take-all' rather than proportional.

I think we (MMP and I) both converged on the "each constituency gets two MPs" because we're both responding to the same perceived demand, in Canada at least, for equal distribution of political power among constituencies in Parliament.

I'll concede that my statement did simplify reality. I also recognize there may be some situations where the opposition can team up with parties in a governing coalition to get something passed that one of the 'main coalition partners' opposes - I think there were a few cases where that happened since the last election, but can't recall which.

But I think the general idea, that you need a majority in order to get anything done, and no more than a majority to get something done, still stands - confidence of the HoC, and bills in general, are both measured by majority votes. So a group that has a majority of seats effectively wields the full power of the HoC, as long as they can keep just that majority.

And I think that this continues to be true even in PR.

TBH I picked it arbitrarily. It could be 40%, or 60%. That barrier came from balancing the following:

(emphasis on edits mine for personal preference in distinguishing score-votes from rank-votes)

I'll agree that a national party with those votes is nobody's first choice. But what what those scores do represent is a party that is broadly tolerable or barely passing. Which is a better approval rating than I think most governments get.

I think this is more of a philosophical question of, which of the following is better:

The math of those two options end up both giving equal averages of 48/90.

As a side note, I think the scale of 0 to 9 from my original proposal may not be the most intuitive scale - votes out of 10 would probably have been better - but just about any scale works. The simplest form of Score Voting, Approval Voting, just has a scale of "Agree / Disagree". Like a FPTP ballot, except you can approve of more candidates than one. So having an average support of 51% with Approval ballots maps pretty neatly to "A majority approves"; then Score effectively gives voters the ability to give partial approvals.

Score lets voters support multiple candidates simultaneously, so multiple candidates can have a majority at the same time, so once two or more candidates achieve concurrent majorities, they have to then compete for the largest majority.

Ignoring my 'winner-take-all eligibility threshold', this means that "majority" no longer means "that threshold where you win", it just means "that threshold where some of your supporters probably also supported the other guy too."

Which makes gathering "a majority support" the beginning of the competition, rather than the end.

I hope what I've said about this makes sense and is more clear than in my original post - 'voters support candidates simultaneously' is the keystone of my entire system; if you use a non-Cardinal voting system for the winner-take-all element then you don't get any of "exceed-a-majority" incentive that I describe.

(continued in nested reply)

What's the point of having a seat at a table if a group of 51% form a coalition that has no incentive to listen to you? Sure, your voice is heard, but what use is that if you're not obeyed?

I think this is the main philosophical difference between my system and the "current approach" to electoral reform.

The 'standard representative democratic tradition' tasks elected representatives with coming up with policy to consider all constituents' needs, but my 'gut feeling' on the subject is that the sorts of people capable of becoming elected representatives (ie. politicians) are the least capable of all of us at engaging in good-faith deliberation with the 'other side'. I'm also a bit skeptical of the value of codes of ethics, but maybe I'm just a pessimist from absorbing US political news.

So instead of "election -> representatives deliberate -> policy decided", I take the alternate approach of "representatives campaign -> election -> policy decided", on the basis that with the right electoral system, a "big tent" party could be incentivized to come up with a broadly popular party before the election, and then just be tasked with implementing it after.